Benchmarking Programing Languages

Joel Eager

March 28, 2018

Joel Eager

March 28, 2018

Computers do math quite fast, but how fast? Well, the answer to that question changes quite significantly depending on the programming language being used.

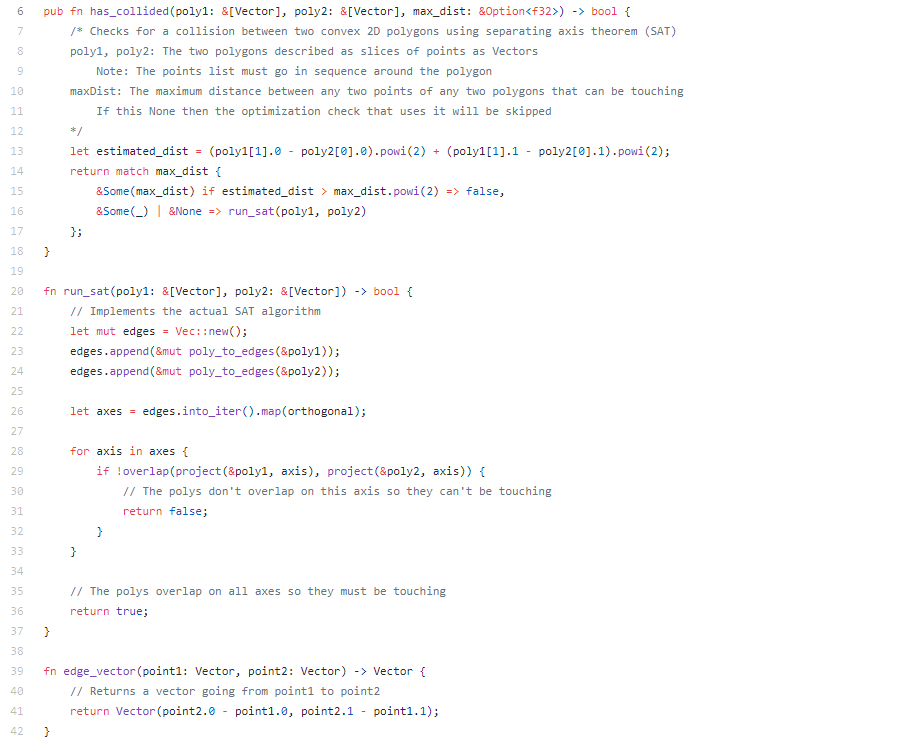

To explore this relationship I implemented a common collision detection algorithm called separating axis theorem in Python, Rust, and Kotlin. This algorithm uses linear algebra to check if two convex 2D polygons are overlapping. Since this is a linear algebra algorithm most of the work is repetitive arithmetic. This makes it a relatively good test of raw execution speed.

Even before running the code I can expect Python to be the slowest since it’s the only interpreted language being tested. Rust, on the other hand, is compiled down to machine code so it should be significantly faster. Kotlin should be somewhere in the middle since it’s compiled but runs in the Java Virtual Machine instead of directly on the hardware.

The metric I’ll be measuring here is the wall-clock execution time. Note that this approach has an inherent amount of inaccuracy due to how operating systems handle process scheduling. However, it’s also the metric that’s most immediately understandable and comparable so it works well for this situation.

The actual program that I’m using takes two objects and sets their center points 100 pixels away from each other. Then one object is moved towards the other in steps of 1 pixel at a time until the algorithm detects collision. This process is then repeated 10,000 times in order to build up a sufficiently long execution time to get an accurate comparision.

Here are the results from running this test. Note how Kotlin and Rust have fairly similar results even though Kotlin runs in the JVM.

| CPU used for the test | Time for Python | Time for Kotlin | Time for Rust |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intel Core i7-8550U | 21.800 seconds | 0.308 seconds | 0.230 seconds |

| AMD A10-6800K | 40.617 seconds | 0.767 seconds | 0.465 seconds |

Now this is a pretty naive implementation. The two objects are 10 and 1 pixels across respectively so it takes a lot of iterations before they collide. This algorithm takes the most time to run when the objects aren’t touching so it would be quite helpful if there was a way to skip over at least some of the iterations where they aren’t touching.

It turns out that it’s trivial to calculate a rough estimate of the distance between the two objects by taking one point from each and applying the Pythagorean theorem. Now, this would be a very rough estimate since it doesn’t take into account the rotation or shape of the objects in question. However, if that rough separation estimate is greater than the combined width of the two objects at their widest points then it can be assumed that the objects aren’t touching. In all other cases the program would still have to run the collision detection algorithm as before to get an accurate result.

With this optimization in play the execution times drop significantly. Note that due to the the inherent inaccuracy of the timing method used, the results for Rust on the two computers should be interpreted as roughly equal.

| CPU used for the test | Time for Python | Time for Kotlin | Time for Rust |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intel Core i7-8550U | 8.250 seconds | 0.145 seconds | 0.033 seconds |

| AMD A10-6800K | 15.844 seconds | 0.346 seconds | 0.027 seconds |

Even though Python is quite slow in comparison to Kotlin and Rust, it turns out that it’s still easily fast enough to do this math in real time for a game. In fact the very Python code I tested here is used in game server of my pyTanks project to check for collisions between the game objects. This just goes to show the trade off that exists with interpreted languages. While they may be more convenient to work with you’re paying the price for that convenience in the execution speed.

If you’re interested in playing with these programs yourself you can find the Rust version here and the Kotlin version here. The Python code is part of the server portion of my pyTanks project here. Specifically, the Python script that implements the algorithm is located here in that repository. All of these repositories are under the MIT licence so if you’d like to make use of this code in one of your own projects you’re more than welcome to.

More blog posts